All photographs in this post (c) Saffron Walkling, 2010

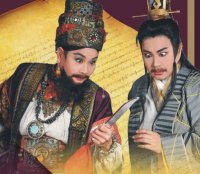

Hamlet: That is the Question was put on by the Richard Schechner Center for Performance Studies at the Shanghai Theatre Academy (STA), and directed by Benjamin Mosse and Richard Schechner (the studio theatre of the Teatrul National ‘Marin Sorescu’, Craiova, Romania: 28th April, 2010)

Continuing from my previous post, which looked at the larger re-imagining of the play by STA, this post will focus primarily on the characterisation of three protagonists, Hamlet, Horatio and Ophelia, and give a brief description of the setting for their interactions.

This was a ‘spoken drama’ production, in Mandarin, with a contemporary, urban set. Shaven-headed Claudius (Zheng Xing) may have entered in a military uniform, speaking like an official making a political speech, but it wasn’t long before he had stripped down to his unbuttoned red silk shirt, a tattooed and red-haired Gertrude hanging on his arm: a gangster king and his moll in a gangster court. The spotless white of the set, pristine apart from a few drops of blood dripping from the ceiling that had missed the bucket placed to catch them, gradually became scuffed and scarred by the action that unfolded. Throughout the performance, various characters mopped away, in increasingly futile attempts to remove the dirt. Fortinbras was cut out altogether in this version, but corruption was foregrounded.

Hamlet

Hamlet (Xue Guanglei)

Hamlet (Xue Guanglei) wasn’t Zhang’s Confucian hero (Shakespeare in China, 1996). He was neither an intellectual nor an incorruptible outsider in this court, nor did he appear to have any ‘sense of political responsibility’ (213-4). In fact, he reminded me of the arrogant but undeniably cool young man who used to doss around at the back of my class at Shandong University. The wealthy son of a successful businessman, he would mock the majority of the class for their studious ways. ‘Why I to work harder?’ he protested. ‘I will have good job in my father’s company in future.’ Xue’s Hamlet – tall, well-built, prone to violence, dressed in black jeans and an open-necked shirt, a blade tucked into his belt – seemed trapped in temperament, as well as in body, in the limiting worldview of Claudius’ ‘Denmark’, despite the influence of his Horatio. Physically, at least, he resembled his uncle more than his ghostly father, who was played by the same actor as the Player King. Any sweetness in his nature was for Horatio’s eyes only. The interpretation of this relationship was well-handled, despite being a little stereotypical: the macho Hamlet in black and the comparatively slight Horatio in white, and the suggestion that Hamlet’s misogyny, especially in relation to Ophelia, was linked to his sexuality. Hamlet semi-secretly dating Horatio also changed this and other dynamics in the play. Ophelia’s strident pursuit, despite (or because of) her increasing awareness that she was in competition with Horatio, put her on a direct collision course with the Prince of Denmark. On a number of occasions he simply pushed her aside when she deliberately placed herself in his way, but in the ‘Get thee to a nunnery’ scene he threw her to the floor in what looked like a violent, anti-female sexual attack (and Ophelia fought back, only giving up when he threatened rape). At this point, Claudius was able to say without doubt, ‘His love tends not that way.’ He needed no other evidence for the root of Hamlet’s ‘madness’. Finally, Hamlet’s relationship with his mother was noticeably non-Freudian. (The Freudian reading of Hamlet and Gertrude’s relationship is a ‘cultural taboo’ too far, according to Taiwanese scholar Cheung Wai Fong in her work on recent Chinese film adaptations of Hamlet.) Thus, his anger appeared to be primarily on behalf of his dead father, perhaps bringing in a Confucian flavour after all, as filial piety is one of the most important codes in traditional Chinese society. Also, despite Hamlet’s chastisement of his mother, before leaving Gertrude’s closet (literally her walk-in wardrobe) he knelt before her, a son once again showing submission to a parent.

Ophelia

Ophelia (Wang Sainan)

Wang Sainan, the eighteen-year-old undergraduate who played Ophelia, was a universal hit with the audience. Bringing in her dance training, hers was a very physical, but also a very controlled, Ophelia. ‘We’ve had quite a theme of strong Ophelias in these productions,’ Nicoleta commented afterwards. I noticed that Laertes called Ophelia jie jie, which means elder sister. This in itself fundamentally changed the dynamic between herself and her stage brother: as the only woman in the household (her mother being dead) and as the eldest child, she took on the role of 2nd parent, aligning herself with Polonius against Laertes. This was most humorously expressed when poor Laertes, about to board his ship, was spun around between father and sister as they took turns to lecture him. Unlike the Polski Theatre production the night before there was no hint of incest in the family dynamic (see above). As the actress was also very tall, Ophelia often seemed to dominate within the household physically as well as verbally. Hamlet was the only male she couldn’t get the better of, and this power struggle between them – often physically expressed – became increasingly complex in the light of Horatio’s presence. These scenes, and the scenes when she joined Horatio and Bernardo/Marcellus on the battlements to see the ghost, are what reminded Madalina Nicolaescu (University of Bucharest) of the heroine in a post-Liberation revolutionary ballet – something about the strong, angular tilt of Ophelia’s body, the strident, androgynous movements, like the statues outside Mao’s Mausoleum in Tiananmen Square, I thought. The programme notes refer to Ophelia as ‘a smart, ambitious woman,’ trying to ‘master’ (!) the ‘socio-sexual realities of the world she inhabits’, and in the way she did this she stood in strong contrast to the queen. Whereas Gertrude, in her low-cut, slinky dresses, used her sexuality to maintain centrality, Ophelia dressed in the smart trouser suit of a business woman, her pre-madness hair scraped back into a power-ponytail. She was more class ‘monitor’ than foot-bound, oppressed woman, and I am almost certain (if my Chinese is to be trusted) that it was Ophelia who insisted that her father report Hamlet’s madness to the king. Thus her determination to pursue a loveless marriage for her family’s gain and to get herself in between Hamlet and Horatio took on the urgency of a bidding war. Ophelia and Horatio were present for large sections of the play where they would usually be off-stage. Most significantly, she joined her father in the closet scene, thus witnessing his murder first hand. During her subsequent mad scene it was unclear whether the blood stains on her torn shirt came from her own or from her father’s body. Of course, this scene seemed positively restrained after the literal bloodbath of Polski Theatre’s interpretation the night before, but it was nonetheless very powerful and still had its sickening moments, such as when, with a completely glazed expression, Ophelia began to chew strips of bloodied fabric before handing it out, covered in saliva, instead of flowers.

Horatio

Horatio (Sun Qiang)

The presence of Horatio (Sun Qiang), as I have already mentioned, became the main obstacle between Hamlet and Ophelia. Dressed in 1920s whites and creams, the slim, rather beautiful actor (a post-graduate student) immediately suggested Sebastian Flyte, although he turned out to be more Maurice. Everything about him, his clothing, his bearing, his tone of voice, indicated that he belonged to another world from the court, and another world from his boyfriend, Hamlet. It was inevitable that, so long as they remained in the corrupting influence of the court, Horatio’s influence could not triumph. As I said earlier, the relationship between Hamlet and Horatio obviously changed the relationship between Hamlet and Ophelia, making the roots of Hamlet’s misogyny more complex, but it also altered Horatio’s relationship with Ophelia. Horatio, like Ophelia, was on stage for large parts of this production, often just watching the action – he is, after all, the storyteller, ‘the Shakespeare’ (Sun Qiang). But at key moments he also intervened in the action. For example, he pulled Ophelia off-stage, away from Hamlet, after she had just witnessed Hamlet’s murder of her father. This raised the question of: which person was he actually trying to help, Ophelia or Hamlet? It was clearly Ophelia who needed his aid, yet the suggestion was that Horatio was more interested in protecting Hamlet. This in turn raised the larger question: who was having the greater influence on whom? Horatio on Hamlet? Or vice versa? Here, off-stage dynamics also intervened in my reaction to on-stage events. It appeared that Wang Sainan and Sun Qiang were close friends in reality, which made Horatio’s apparent leaving of his ethical senses all the more disquieting.

When a kiss isn’t just a kiss

I’m not sure if it was simply because he was uncertain of his English so early in the day, but at breakfast in the hotel where everyone was lodged, the actor Sun Qiang had seemed as modest and diffident as he was onstage. So it was ironic that he proved to be part of the most controversial element of the production. For when Hamlet met Horatio (Ophelia and Barnardo/Marcellus being conveniently absent), they embraced for just a fraction longer than a Western hetero-normative environment allows. When this was followed by a completely unambiguous gay kiss, I swear there was an audible gasp from the audience… It was like being back in 1987, when Johnny kissed Omar in My Beautiful Laundrette. Another dynamic to this moment in the performance was added by the fact that three representatives of the Chinese Embassy in Bucharest were sitting next to us in the front row. For some people, like retired teacher Joan Griffiths from the UK, the surprise was not in the kiss, but in the fact that it was performed by Chinese actors, going against her expectations of China’s social conservatism. For others it was the kiss that was problematic. Madalina, such a fan of the strong Ophelia, got quite angry about it as we discussed it a few days later, sitting drinking coffee together in Bucharest. ‘What I don’t understand is why they had to actualise it,’ she protested, as if this small action had been as explicit as the moment in the Polski Theatre’s play-within-a-play when two men simulated having sex with the player queen from in front and from behind… ‘It was only a kiss,’ I said. ‘Yes, but why actualise it?’ I felt the opposite. I’ve seen several productions where a relationship between Hamlet and Horatio is hinted at, more where Horatio is played to be in love with an oblivious Hamlet, but this was the first production where I had seen it enacted and sustained throughout a performance, and not only as a sexual relationship but as an emotional one, in fact, as the central love story. Of course, this added a further dimension to Horatio being the only person Hamlet can trust and the only person there to support him. Afterwards, Stanley Wells (editor of the Oxford Shakespeare and Chairman of the Shakespeare Birthplace Trust) said that he, too, had thought the relationship very well done: ‘And it’s all there in the text, you know.’ Interestingly, the physical contact between Horatio and Hamlet throughout the play – holding hands, resting heads on each other’s shoulders, sitting in an embrace – would not necessarily be read as homoerotic in a Chinese context. In 1993, when I was first teaching at Shandong University, it was banned for girls and boys to date as undergraduates, so you never saw mixed couples. However, homosocial intimacy was common. Even now, particularly in more rural areas, you can see young men caress with no sense of this being a potentially sexual action. When we discussed this at the post-production discussion, two female crew members cuddled each other chastely, one sitting on the other’s lap. This cast light on what would otherwise have been a strange comment (to northern European ears, at least, where men rarely touch unless playing sport or being drunk). Xue (Hamlet) said, ‘It is easier for us [to act a gay relationship] because in life we are fast friends, so we can figure out what kind of action to make.’ Sun (Horatio) was quick to add, however, ‘For me the most obstacle is the kiss. In China, in our culture, although we are fast friends it is very hard to do.’ Sun concluded that, because he had to spend so much time acting, but not speaking, playing Horatio was ‘exhausting’ and that, because of the gay kiss, ‘For me it is the hardest part I ever play.’ This aspect of the performance clearly traumatised him off-stage, although it was not evident at all on-stage, and he related it again and again to being Chinese. That Horatio was so difficult for him to play was surprising, however. Afterall, he had acted in a student production of Sarah Kane’s Blasted the year before…