Short Presentation Outline: Richard III workshop, YSJU

Watch the National Theatre of China’s Globe to Globe Richard III at The Space (No longer available)

See a clever clip from Sabab’s Richard III: An Arab Tragedy at Global Shakespeares (Available)

Watch the London Olympics Opening Ceremony on the BBC (No longer available)

Danny Boyle framed his Olympic Opening Ceremony with two bastions of British culture: Mr Bean and William Shakespeare. In fact, in some circles (China, Palestine) the World Shakespeare Festival, part of the Cultural Olympiad, has been renamed Shakespeare’s Olympics… This year of sport has also been a year of the arts, in the shape of the London 2012 Festival, and at the heart of this has been ‘our’ National Bard. Not only did the Olympic and Paralympic Ceremonies use The Tempest to showcase our culture to the world, however; it also assumed that the world would respond to this because Shakespeare is somehow ‘universal’.

There is a very important conversation to be had here about colonial indoctrination, cultural ownership, and Shakespeare as a global brand: however, I cannot do this justice in 15 minutes, and for the time-being at least I want to celebrate the brilliant carnivalesque of this festival, which attempted to recreate – in reverse – the experience of the English Players who took Shakespeare into Europe in the 17th century and performed in English to audiences who, often-times, could not understand a word that was being said! Yet many of those cultures now claim Shakespeare as their own. Not so much a National Bard as a bard of many nations.

Globe to Globe was part of the larger WSF, and presented all 37 plays – in 37 languages. Artistic director, Dominic Dromgoole, and Globe to Globe director, Tom Bird, set out their understanding of what this festival signified in the festival programme: ‘Shakespeare is the language that brings us together better than any other, and reminds us of our almost infinite difference, and of our strange and humbling commonality’ (Dromgoole and Bird, 2012). Shakespeare is a universal or shared language, they imply – yes, he reminds us of difference but mostly he emphasises our commonality. However, in an article in the same programme, the academic Dennis Kennedy challenges this idea of universality. Shakespeare has travelled so far, he argues, because of his ‘flexibility.’ We use a specific word to describe Shakespeare adaptation in this context: appropriation. Much as Shakespeare did with the European and Classical sources he appropriated for his own plays, theatre practitioners across the world have taken Shakespeare and used him for their own purposes. Part of this transformation often involves leaving the language behind, challenging the claim that Shakespeare is his language.

First of all, let’s look at the National Theatre of China’s production which wowed audiences at the Globe last April (see my long review here). This was another extremely rainy month, as some of you will remember, nearly as rainy as now, and as flooded. I mention this because the company had found itself without costumes and props. Having sent them ahead by sea 7 weeks earlier, the English weather prevented the container ship from entering Felixstowe harbour, so the actors had to make do with borrowed robes – and a couple of costumes hastily run up, such as this yellow coat. Not quite the Imperial silk that had been planned, but its colour still indicated to anyone who knows anything about Chinese history that whoever wore it was the Emperor.

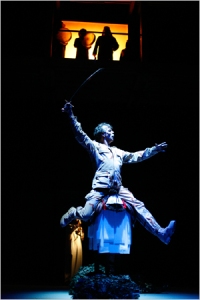

Yet critics unanimously agreed that the performance was so strong and so innovative that the lack of costumes made little difference. For this Sinocized appropriation relocated late medieval England to ancient China. Nimbly side-stepping some Western commentators’ hopes that the production would critique the power politics of modern China, it instead entranced British audiences with its clever interweaving of Shakespeare’s story with traditional Chinese theatre. Although largely ‘spoken theatre’, it incorporated Beijing Opera traits: during Richard’s brilliant seduction of Lady Ann (when she spat in his face he rubbed it in as if it was aftershave), she sang a stylized aria in the high-pitched voice of female roles. Later, the same actress doubled as the young Prince Edward. Now she danced with a riding crop, indicating that the prince was riding on horseback. This non-naturalistic technique of Beijing Opera influenced the theory and practice of a certain German dramaturg at the beginning of the 20C – Bertolt Brecht’s defamiliarization/alienation effect, which you’ll recognise in much experimental theatre. Two other characters were borrowed from Chinese Opera. The murderers were chou, or clown figures, engaging in Chinese style cross talk and acrobatics as they debated whether or not to murder Clarence. This worked well with Shakespeare’s text as there is a grotesque comedy in this scene on the English stage, too. However, they added a twist to the usually sinister Tyrell when they reappeared in this role, one sitting on the other’s shoulders. Again grotesquely comic, this time in tension with a traditional Western interpretation of the character, they acted in conscienceless unity.

In Li Ruru’s review on the Shakespeare’s Globe Blog she explores how this production, combining both spoken and sung theatre traditions is not only intercultural, however – it is also intracultural. She also discusses their interpretive choice to present Richard without any physical deformity.

Director Wang Xiaoying spoke of his influences and aims in an interview he gave in China: “I saw the original Richard III play last year in Beijing starring [Hollywood actor] Kevin Spacey, which was fabulous and remained true to Shakespeare’s original work. However, the WSF is a platform for different countries to showcase their own culture. I believe that other countries will also fuse unique cultural elements into Shakespeare’s plays”( cited in Wang Shutong, Global Times, 2012).

The production had been specially created for Globe to Globe to “bring Chinese culture out to meet with the world’s different races, different languages, and different cultural backgrounds, to interact and communicate with one another under the banner of Shakespeare.” (Wang Xiaoying cited in Lee Chee Keng, Shakespeare’s Gobe Blog, 2012).

I would like you to stop and think about this idea of being ‘under the banner of Shakespeare’. What do you think he means?

Square Word Calligraphy: look carefully and you’ll see it’s in English…

(c) National Theatre of China

The second production was introduced by Anglo-Kuwaiti director, Sulayman Al-Bassam, as part of the ‘It is the East’ study sessions. Al-Bassam was brought up in the UK (his mother is English, his father Kuwaiti) but since the 1st Gulf War he has increasingly felt he should fashion himself as an Arab voice. Originally adapting Shakespeare’s plays into an Arab setting, but still in English, his RSC commissioned Richard III: An Arab Tragedy was performed in Arabic.

As Kennedy noted of Shakespeare under communism, he can often be an agent under deep cover…. (Foreign Shakespeare, 1993) Because Shakespeare’s texts are classic and foreign they can be a way to sneak messages to audiences without the censors realising. Al-Bassam discussed how in the Arab world there is both political and cultural censorship at times. Shakespeare is about Britain and the British, right? Or at least, about Westerners? There can’t be any harm in that?

Wrong.

Al-Bassam’s Richard III, performed by his company Sabab, was overtly political and Richard looked very like a Saddam figure. In fact, he loves to announce, he once had Syria’s Bashar al Assad in the audience. When al Assad heard the name of an imprisoned Syrian dissident mentioned by one of the actors, he had a Claudius moment, almost calling for ‘Lights!’ before he and his entourage stormed out. ‘Hence the utility of our friend, William Shakespeare, you know? It’s William Shakespeare who’s saying this, not us.’ (Al-Bassam in interview with Brown, for PBS, 2009)

This adaptation was much, much darker than the comically entertaining Chinese appropriation – and when the Western funded ‘Tudors’ took over at the end there was no sense of order being restored. This production has been written about by Graham Holderness here and blogged on by Margaret Litvin on her fabulously wide-ranging and up-to-date Shakespeare in the Arab World (put Richard III into her blog’s ‘search’ box and it will take you through to several posts).

At the It is the East Study Day at the Globe, Al-Bassam also talked in great detail about how, if these reconfigurings were going to work in the new context, the equivalences had to be very carefully thought through. How can you present Clarence drowned in a butt of malmsey wine if you are presenting him as a devout Muslim? In a chilling clip, he showed us exactly how. As the muezzin called worshippers to prayer, Clarence entered carrying a suitcase. He paused, knelt down and opened the suitcase, which was full of water. Then he began his ritual ablutions, cleansing himself for prayer. The murderer had no shifting consciences as he held his victim’s head under the shallow water. As one of our students noted, this parallels the religious significance of wine in western culture: as the blood of Christ, wine creates communion with God through atonement.

So don’t believe it when people say Shakespeare is irrelevant in today’s world… Or that he’s the Bard of Britain…

This is just a taster of some of the productions that are out there, and some of the discussion points around intercultural Shakespeare. My article on WSF Arab Shakespeare is available on the Year of Shakespeare blog, as well as being archived here under Globe to Globe. Please add comments to this blog post if you have any.

Pingback: The Year of Ricardo: Richard III in Argentina | Shakespeare Travels © Saffron Walkling